Later influences of Epona

Epona may have influenced later deities, including Rhiannon, Macha and perhaps also representations of the Virgin Mary.

Rhiannon

Rhiannon (pronounced REE an-on) is an otherworldly being described in the mediaeval Welsh tales The Mabinogi of Pwyll Prince of Dyfed and The Mabinogi of Manawydan ap Llyr.

Names and titles

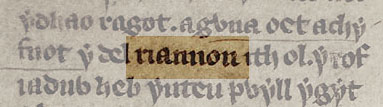

In the Old Welsh original her name is spelled Riannon [Rhydderch]; the now customary Rhiannon probably came about when Old Welsh texts were translated to modern Welsh for the Welsh to English translation of Lady Charlotte Guest.

Spelling 'riannon' in the White Book of Rhydderch

Rhiannon is plausibly linked to Epona by her name and title. At Alba Iulia (Alba, Transilvaniei, Romania) is a dedication 'Epon(a)e Regin(ae) Sanc(tae)' (to Holy Queen Epona) [CIL 3 #7750, Cserni, Reinach 1895 #117]; at Ulcisia Castra (modern town of Szentendre, Pest County, Hungary) is a dedication 'Eponae Reginae' (to Queen Epona) [AE 1973 #438] and at Duklja (Montenegro, former Yugoslavia) are a further two dedications 'Epon(a)e Regin(ae)' (to Queen Epona) [AE 1897 #5, CIL 3 #12679, Schallmayer #488], [AE 1933 #76]. These inscriptions are in Latin; in Gaulish, Queen as an epithet would be 'Rigatona' (pronounced REE at-on-a) [Delmarre p.258]. Old Welsh is derived from Gallo-Brittonic, which is believed to be identical to Gaulish [Lambert]. In the evolution from Gallo-Brittonic to Old Welsh, one of the sound changes is that soft 'g' between vowels vanishes [Watson p.5]; thus Gallo-Brittonic Rigatona would produce thus Old Welsh Riannon and modern Welsh rhiain, rhianedd (lady, ladies) [Gruffydd p.98]. This gives the first of three links between Rhiannon and Epona, her name or title.

Divine and otherworldly

To see the second link, we need to consider the story of Rhiannon as told in the first and third branches of the Mabinogion. From the translation by [Parker]:

As they were seated, they could see a woman on a large stately pale-white horse, a garment of shining gold brocaded silk about her, making her way along the track which went past the mound. The horse had an even, leisurely pace; and she was drawing level with the mound it seemed to all those who were watching her.

In the footnotes, Parker makes a connection between the 'even, leisurely pace' and the typical pose of sidesaddle Eponas, at a walk with one foreleg raised. This gives a second link between the literary description of Rhiannon and the iconography of Epona, both riding a horse at a slow walk.

The colour of Epona's horse and of Epona's cloak is unknown - many of the depictions are known to have been painted, but apparently no paint analysis has been published. It is not known whether the other details such as colour match with Epona. So, sometimes Epona is assumed to ride on a white horse; but this is an assumption based on the story of Rhiannon, and cannot be taken as a link between them.

Epona is a Goddess, and there are several indications that Rhiannon is not mortal but is, at least, otherworldly. Firstly, Pwyll is sitting on the mound in hopes of ‘witnessing a marvel’ and sees Rhiannon. Secondly, she is only seen, on each of three successive days at the mound, at a particular time of day ‘After the first course’ of the evening meal - at sunset? Thirdly, a curious phrase is used Ar uryt y neb a’y guelei ‘on the mind of anyone that would see her’, as if they saw with their mind rather than their eyes. Fourthly, she is radiantly beautiful, ‘And he realized at that moment the faces of every woman and girl he had ever seen were dull in comparison to her face’. Most obviously, however, is that Pwyll and his attendants cannot catch up with her, even by running or by riding the fastest horses, while her slow and steady pace never varies:

‘Lord,’ said he ‘it is no use following that Lady over there. I haven’t known any horse in the land faster than this one, but [even on this] following her was to no avail.’

‘Aye’ said Pwyll ‘there is some kind of a magical meaning to this. Let us go [back] to the court.’ [Parker]

And later on

Her pace was no different from the day before. He [too] put his pace at an amble, supposing as he did that however slowly his horse went, he might be able to overtake her. But it was no use. He loosed his at the reins, but got no nearer than if he had been on foot; and the more he beat his horse, the further away she became. [Yet] her pace was no greater than before. [Parker]

Care and breeding of horses

A further connection between Rhiannon and Epona is care for, and breeding of, horses. We have seen that horses figure in the story so far, but this is not specific - many people ride horses. The manner in which Pwyll catches up with Rhiannon demonstrates a care for the welfare of a horse:

He spurred on the horse as fast as it could go. But he saw it was useless following her [in this way].

Then Pwyll spoke: ‘Maiden,’ he said ‘for the sake of the man you love the best, wait for me!’

‘Gladly I’ll wait’ said she ‘but it might have been better for the horse if you had asked me a good while before.’ [Parker]

Identification with horses

Much later in the story, two narrative threads are thoroughly intertwined: Rhiannon giving birth to a child and a magical mare giving birth, on the same day, to a foal. To summarise: Pwyll, the husband of Rhiannon, is under social pressure to prove his fertility and asks for one year to produce an heir. Rhiannon becomes pregnant but mysteriously looses her son during the night she gives birth; elsewhere a hero Teyrnon thwarts the theft of the foal of a magical mare which foals each Beltane, and in the process finds and adopts Rhiannon's missing son. The child and the foal grow up together for three years; meanwhile, Rhiannon is falsely accused of the death of her son and as punishment is made to act as a horse, carrying visitors to the castle. Eventually, the son is returned to Rhiannon and her punishment ceases.

Similarly in the tale of Manawydan ap Llyr, where Rhiannon is married to Manawydan and is then imprisoned by the magic of Llwyd Cil Coed, the punishment of Rhiannon has an equine component:

‘Pryderi would have the gate-hammers of the court around his neck, and Rhiannon would have the collars of asses, after they had been carrying hay. Such was their imprisonment.’ [Parker]

Conclusion - Epona/Rhiannon links.

We have seen links by name and title, by association with horses, fertility and foals. The stories of Rhiannon seem to be an echo of an earlier, divine figure. It is likely, therefore, that the (now lost) tales of Epona, and her titles and attributes, were a formative influence on the later British and ultimately Welsh stories of Rhiannon.

Macha

The story of Macha is described in the 12th century Leabhar na Nuachongbhála (Book of Leinster), which is archived as MS 1339 at Trinity College, Dublin [Leabhar].

Macha is one of The Morrigan - a triad of goddesses of 'war, death, and slaughter' [Mowat]. In early mediaeval Irish mythology, the three Machas were associated with both war and fertility [Green 1986 p.101; Gulermovich-Epstein, unpaged, section 'Macha'] — similar associations to the military and non-military spheres of Epona.

There is an additional link to horses in that Macha is made to run in a race against the horses of Conchobar, king of Ulster while pregnant [Leabhar]; she gives birth to twins after winning the race, while also cursing the men of Ulster to birth-pangs in time of need. This connection is however circumstantial and indirect - war and fertility are attributes of a great many deities. It would be rash to propose a direct link between Macha and Epona, particularly given the large separation in time (8 centuries) and space (Ireland was never part of the Roman Empire). A link between Macha and Rhiannon is closer in both time and space, and rather more probable.

Mary and the flight to Egypt

Autun, in antiquity Augustodunum, was the civitas of the Aedui [coll. 1987], replacing the oppidum of Bibracte from the first century CE onwards [Goudineau]. Both sites are firmly in the first zone of Epona representations.

This statue, a capital of one of the pillars in the cathedral nave, represents Mary, Joseph and the infant Jesus fleeing from Herodias to Egypt. The core of the current cathedral was constructed in the years 1120-1135, the site dating to the 5th century CE.

The iconography here is strongly influenced by Epona representation - the steady gait with raised foreleg, the sidesaddle stance. However, the horse or ass is now directed by a male figure rather than by the woman, and the foal has become a human child. The sweep of cloak around the head has become a halo.

References

Année Epigraphique (1897), #5

Année Epigraphique (1933), #76

Année Epigraphique (1973), #438

Collectif, (1987) Autun Augustodunum, Capital des Éduens. Autun, Ville d'Autun Musée Rolin.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), 15 volumes

Cserni, B. (1908) Alsöfehémegyei Történelmi Rég. Évk. 14 p.45

Delamarre, X. (2003) Dictionnaire de la Langue Gauloise. 2nd edition, Paris, Editions Errance.

Goudineau, C. and C. Peyre (1993). Bibracte et les Eduens: à la découverte d'un peuple gaulois. Paris, Glux-en-Glenne. Editions Errance; Centre archéologique européen du Mont-Beuvray.

Green, M. (1986) The Gods of the Celts. Gloucestershire, Sutton Publishing Limited.

Gruffydd, W.J. (1953) Rhiannon, an enquiry into the origins of the first and third branches of the Mabonogi. Cardiff, University of Wales Press.

Gulermovich-Epstein, Angelique (1998) War Goddess: The Morrígan and Her Germano-Celtic Counterparts. PhD thesis, University of California at Los Angeles. electronic version, #148, September 1998.

Lambert, P.-Y. (2003) La langue gauloise. Paris, Editions Errance

Leabhar na Nuachongbhála. Available online as a series of scanned images at the Irish Script on Screen (ISOC) project. Select Trinity College, Dublin and then MS 1339.

Mowat, Catherine (2003) The 'Mast' Of Macha: The Celtic Irish And The War Goddess Of Ireland. Barbara Roberts Memorial Book Prize Winner.

Parker, W. (in press) The Four Branches - Celtic Myth and Medieval Reality. The annotated translation is available online

White Book of Rhydderch (Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch). National Library of Wales, Peniarth MS 4. A photographic record of this MS is available online.

Reinach, Salomon (1895, 1898, 1899, 1902, 1903) Épona. Revue archéologique 1895, part 1, 113, 309. Addenda ibid 1898, part 2, 187; 1899, part 2, 61; 1902, part 1, 227; 1903, part 2, 348.

Schallmayer, E. (1990) Der römische Weihebezirk von Osterburken 1, Stuttgart, p. 384

Watson, W.J. (1926) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Republished 2004, Birlinn Ltd, Edinburgh. ISBN 1-84158-323-5